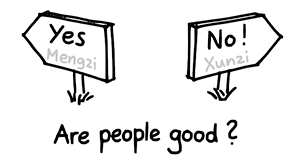

Xunzi vs. Mengzi – Are People (No) Good?

About 2300 years ago, the great Chinese thinker Xunzi 荀⼦ wrote: “Human nature is bad“.

But he wasn’t just having a bad day.

The question—Are humans fundamentally good or bad?—is a major fork in the road. How you answer this question profoundly impacts your morals and how you live your life.

Previous to Xunzi, another famous scholar had claimed that human nature was inherently good.

Mengzi 孟子: Human nature is good

The Ox Hill

Mengzi had illustrated his idea with a story about a wooded hill. After the trees get chopped down and the sprouts are grazed by animals, the hill appears barren and unfruitful.

He compares this hill to someone who can’t bring forth his good character under bad circumstances. For him, goodness is an integral part of every person’s nature. It merely requires the right circumstances to emerge.

Goodness will grow forth naturally from every person if no one interferes.

Willows and Bowls

Someone suggested to Mengzi that a good character had to be forged from a man’s nature like bowls were made from a tree.

Mengzi objected that a tree must be violated in order to be turned into useful bowls. He can’t accept the comparison between the creation of bowls and the cultivation of a good character, because force is not the way to bring goodness out of people.

Mengzi’s position is clear: Humans are inherently good. And if they are not, the circumstances and society are to blame.

Xunzi 荀子: Human nature is bad

Now when Xunzi responds to the claim that human nature is actually bad, we should not mistake this statement as misanthropic. In fact, he doesn’t claim that all humans are bad. It is just their natural disposition that is bad.

The problem is that humans desire immediate gratification. They hate anything that doesn’t serve their needs.

Our nature is not bad in the sense that we want bad things to happen. Rather it is our greed that causes chaos, conflict and immorality.

This is why—and Xunzi repeats this sentence multiple times—human nature is bad. And it requires conscious effort to be good.

The function of rituals and values

Following the tradition of Confucius, Xunzi reasons that the badness of human nature required wise kings to establish moral rituals li 禮 and values yi 義.

The sage kings had recognised that states without rituals and values sink into conflict and chaos.

After all, humans compete for scarce goods and would fight for them relentlessly—if it weren’t for rules and restraints.

Xunzi compares the sages to craftsmen, who, with effort, bring out something precious from raw material. A crooked piece of wood needs to be bent in order to be useful.

If it weren’t for the wise kings, their laws, penalties and orders, the strong would exploit the weak and the majority would oppress minorities.

If human nature was good, we wouldn’t need these rituals and values.

The desire for betterment

Another argument for the badness of human nature starts with the observation that desire always originates from some sort of deficiency. For example, a poor person desires wealth and an ugly one beauty. One tries to acquire only those things from the outside which can not be found within oneself.

Humans feel a desire to be good. They don’t enjoy their badness, and because of their lack of goodness, they strive for betterment. This desire for goodness reveals that the human starting point is a bad natural disposition.

Culture over Nature

And this is precisely what Xunzi considers the exceptional quality of mankind: Humans are capable of rising above their bad disposition. They can resist their urges, give others the advantage and set aside their own needs in favour of the common good. This is best achieved under the guidance of suitable teachers, following the tradition of rituals and values, which means: by following convention rather than intuition.

People have a choice to remain a petty person xiao ren ⼩⼈ or become a noble person junzi 君⼦. It is up to us to become good.

We can very well describe Xunzi’s position as optimistic. Given that people have access to good teachers and role models, their goodness does not depend on optimal social or political circumstances, but only on their effort to overcome their inherently bad nature.

Why this is important

The tension between a belief in natural innocent goodness and the conviction that our bad disposition needs cultivation echoes through human history.

Thomas Hobbes might come to mind, who was convinced that a strong state was necessary to constrain the beastly nature of man. He finds an opposite voice in Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who glorified the allegedly noble mind of the uncivilised man.

The difference may seem minor, but it is in fact massive.

Here’s the thing: If we assume that humans are inherently good, then all our troubles can be attributed to the environment.

Therefore the world is to blame, not oneself. As a consequence, we want to change “the world” rather than ourselves. This attitude opens the door to our worst tyrannical impulses.

On the other hand, if we acknowledge that humans are fallible, we see that goodness must be cultivated. We understand that the cause of our troubles may lie within us—not necessarily in the world.

Mengzi had blamed the external world for our problems. Xunzi on the other hand sees them within ourselves. For him, our job, first and foremost, is to fix ourselves.

When you observe badness in others, then examine yourself, fearful of discovering it.

Xunzi 荀子, Chapter 2

If you want to dig deeper

- Xunzi, Xunzi

- Mengzi, Mengzi

- Bryan Van Norden, Introduction to Chinese Philosophy

Before you go

If you enjoyed this article, then subscribe to my mailing list to receive more animated stories!

Great work as always, but I want to point out something that could be corrected. When talk about rituals, I think 禮義 should be 禮(lǐ) 儀(yí).

Thank you so much! Fixed it.

Happy New Year Ralph!

Thank you, this was great to read and to think about.

Best from Venezuela.